- Home

- Scans for Women

- Scans for Men

- Msk

- Pregnancy

- Cardiovascular

- About

- Book a Scan

- Blog

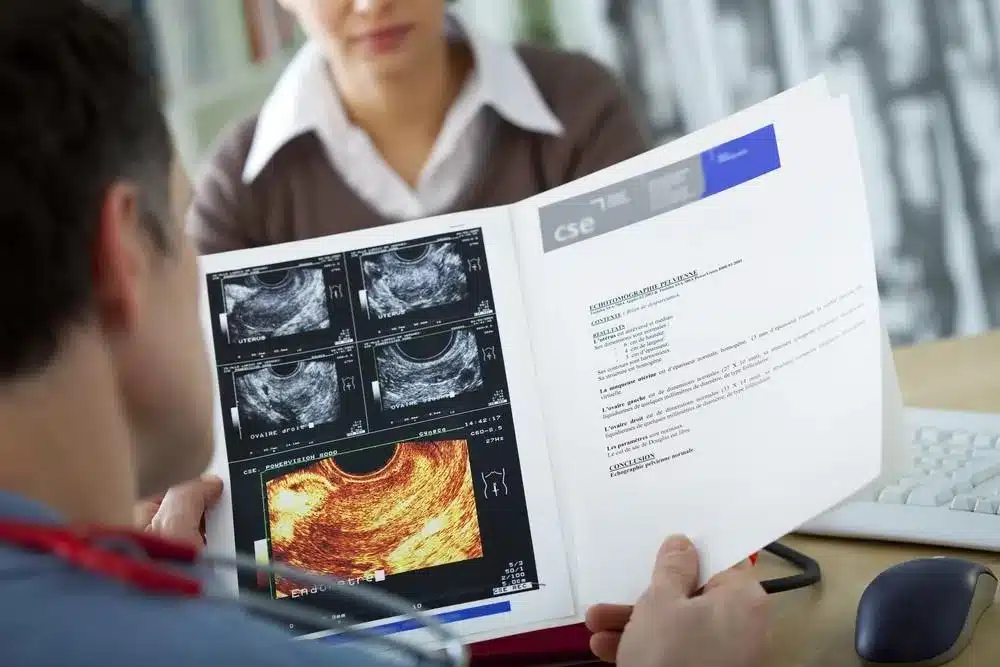

A transvaginal ultrasound scan is one of the most common ultrasound examinations, regularly used to identify any pathology related to the female reproductive system. You have probably visited your doctor, who has requested a pelvic ultrasound. What can you expect?

The most common reasons for a pelvic ultrasound examination are:

- Pelvic pain

- Abnormal uterine or vaginal bleeding

- Check the status of a pregnancy

- Evaluating the cervix during pregnancy

- Family history of ovarian cancer or some other risk for ovarian cancers, such as BRCA mutations.

We will look closely to some of these symptoms later in our blog.

Ultrasound is like any other medical imaging test. If you have your scan in the NHS, It must be prescribed by your doctor. You can't go to an ultrasound department and request that they scan you. There has to be a medical indication.

In a private ultrasound clinic such in Sonoworld, you do not need a doctor's referral. The simple reason is that pain or any symptoms are a clinical indication.

When the ultrasound appointment has been scheduled, you will probably be told that you need to drink some water and not empty your bladder. This is important because your uterus resides behind your bladder and when the sonographer is scanning you from your abdomen, a full bladder is necessary to visualize your uterus and ovaries. In some departments and private clinics, you will not offered a transabdominal scan but a transvaginal scan.

The sonographer will come to the waiting room and call out your name, usually just your first name or last name. By now you will probably need to empty your bladder, but your technologist is aware of your discomfort and will be as efficient as possible.

Once you are in the exam room you will be asked to lie on your back on the exam table and lower your pants and underwear just a bit.

The sonographer who will perform the ultrasound scan will apply some ultrasound gel to the transducer and begin scanning your lower abdomen. Please let the sonographer know if he or she is pushing too hard.

Ultrasound works by transmitting high-frequency sound waves through the transducer. The transducer then listens for those returning echoes coming from the tissues inside your body. Ultrasound looks at soft tissue organs but is unable to evaluate intestines or bone.

The sonographer will be taking images of your uterus and ovaries, measuring them, and making note of any abnormalities.

Normally there are two parts to having a pelvic ultrasound. The first part is the abdominal scan which was just described. The second part is called an endovaginal or transvaginal ultrasound (through the vagina). A transvaginal ultrasound probe works the same way as the abdominal probe does but it's long and thin. It is generally a higher frequency probe which means that it generates images of a higher resolution and is closer to the uterus and ovaries once inserted into your vagina. Think of the forest and the trees. The abdominal scan looks at the forest giving an overall view of your pelvis. The vaginal scan looks at the individual trees (uterus and ovaries) in greater detail.

If you haven't been sexually active a vaginal ultrasound is not usually performed.

The vaginal ultrasound probe will be covered with a condom and will have been soaked in a disinfectant between uses.

The good news is that you have to have an empty bladder for the vaginal ultrasound. The sonographer will ask you to use the bathroom and empty your bladder completely. As important as it was that it be full for the abdominal part, it's equally important that it be empty for the vaginal part.

If you're having bleeding and are wearing a tampon, you will need to remove it. If you're bleeding heavily just let the sonographer know so that an absorbent pad will be placed on the couch for you. Don't be embarrassed. Their only interest is trying to help you and your doctor to figure out what problems there might be.

Some ultrasound exam rooms have tables equipped with stirrups on the table. The will be in place and you will be asked to put your feet in them and slide all the way down to the end of the table. If the table doesn't have stirrups, you may be asked to place a pillow or a booster pad under your hips so that they are propped up or you might have to slide to the end of the couch and place your feet on a chair.

The sonographer will insert the probe, or ask you to do it. It isn't painful and isn't much bigger than a tampon. The technologist will move the probe around taking pictures of your uterus and ovaries, measuring them, and documenting any abnormalities. You may hear sounds similar to a heart beat. The sonographer is using Doppler ultrasound to demonstrate that there is normal blood flow in your ovaries.

After taking all the necessary pictures the sonographer will remove the probe and remove the booster from under your hips or ask you to take your feet out of the stirrups and make yourself comfortable.

The ultrasound practitioner called sonographer in the UK or technologists in the USA is a highly trained medical professional. They are fully qualified in most cases with post-graduate degrees. In the past, many sonographers were trained on the job. Today a technologist must go to an accredited university and complete either a post-graduate degree or a Batchelor in Medical ultrasound.

Sooner or later, as women, most of us experience some degree of pain in our pelvic region. How we respond to pain varies among us, some women are more bothered by pain than others. If pelvic pain is severe enough to disrupt your daily life for either a few days a month or for longer amounts of time, if pelvic pain increases over time, or if you have experienced a recent increase in pain, you should talk with your healthcare provider to determine the cause.

There can be many causes of pelvic pain, so be prepared for a long diagnostic process. Many times there is more than one reason for pelvic pain and it can be difficult to pinpoint the exact source. It may be necessary for your consultant to consider other parts of your body when determining the cause of pelvic pain. Pelvic pain can be caused by problems in the digestive or urinary systems, as well as the reproductive organs.

To help your doctor diagnose the cause of your pelvic pain, it's important that you can answer a few questions:

1. When did the pain begin?

2. Is it constant pain, or does it come and go?

3. How long does the pain last?

4. How severe is the pain?

5. Is it a sharp stabbing pain or a dull ache?

6. Is the pain always in the same place?

7. When do you typically experience pelvic pain?

Acute pelvic pain is pain that starts over a short period of time anywhere from a few minutes to a few days. This type of pain is often a warning sign that something is wrong and should be evaluated promptly.

Pelvic pain can be caused by an infection or inflammation. An infection doesn't have to affect the reproductive organs to cause pelvic pain. Pain caused by the bladder, bowel, or appendix can produce pain in the pelvic region; diverticulitis, irritable bowel syndrome, kidney or bladder stones, as well as muscle spasms or strains are some examples of non-reproductive causes of pelvic or lower abdominal pain. Other causes of pelvic pain can include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), vaginal infections, vaginitis, and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). All of these require a visit to your healthcare provider who will take a medical history, and do a physical exam which may include diagnostic testing such as an ultrasound scan and blood tests.

You can have these imaging tests for free in the NHS or you can choose to have a private ultrasound in London and your screening blood tests in our private clinic in Harley Street.

Women who have ovarian cysts may experience sharp pain if a cyst leaks fluid or bleeds a little, or more severe, sharp, and continuous pain when a large cyst twists. Fortunately, most small cysts will dissolve without medical intervention after 2 or 3 menstrual cycles; however large cysts and those that don't rectify themselves after a few months may require surgery to remove the cysts.

An ectopic pregnancy is one that starts outside the uterus, usually in one of the fallopian tubes. Pain caused by an ectopic pregnancy usually starts on one side of the abdomen soon after a missed period and may include spotting or vaginal bleeding. Ectopic pregnancies can be life-threatening if medical intervention is not sought immediately and this is why at Sonoworld we offer the same day early pregnancy scan. The fallopian tubes can burst and cause bleeding in the abdomen if left untreated. In some cases, surgery is required to remove the affected fallopian tube.

Chronic pelvic pain can be intermittent or constant. Intermittent chronic pelvic pain usually has a specific cause, while constant pelvic pain may be the result of more than one problem. A common example of chronic pelvic pain is dysmenorrhea or menstrual cramps. Other causes of chronic pelvic pain include endometriosis, adenomyosis, and ovulation pain. Sometimes an illness starts with intermittent pelvic pain that becomes constant over time, this is often a signal that the problem has become worse. A change in the intensity of pelvic pain can also be due to a woman's ability to cope with pain becoming lessened causing the pain to feel more severe even though the underlying cause has not worsened.

Women who have had surgery or serious illness such as PID, endometriosis, or severe infections sometimes experience chronic pelvic pain as a result of adhesions or scar tissue that forms during the healing process. Adhesions cause the surfaces of organs and structures inside the abdomen to bind to each other.

Fibroid tumours (a non-cancerous, benign growth from the muscle of the uterus) often have no symptoms; however, when symptoms do appear they can include pelvic pain or pressure, as well as menstrual abnormalities.

Due to a large number of possible causes of pelvic pain, the diagnosis begins by process of elimination. Your doctor may order several types of tests to diagnose the problem. It may seem tedious and time-consuming; however, this approach is the best way for your provider to determine the cause of your pelvic pain. Some of the tests that your physician may order include ultrasound imaging, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and various bowel tests. However, these tests cannot detect endometriosis or adhesions and laparoscopy may be necessary to diagnose the cause of your pelvic pain.

What type of treatment you receive depends on the diagnosis. Treatments can vary from medications for urinary tract infections (UTI) or vaginal infections to pharmacologic treatment in the hospital for serious infections such as PID. If a sexually transmitted disease is diagnosed, your partner will also need to be treated to prevent reinfection.

Menstrual cramps can often be relieved with drugs that reduce inflammation, such as ibuprofen which blocks the production of prostaglandins that cause the uterus to contract. Sometimes the diagnosis will require the use of hormonal therapies including oral contraceptives and other types of hormones. Antidepressants are helpful for some women because they help break the cycle of pain and depression that often occurs in women with chronic pelvic pain.

Surgery may be the answer for certain types of pelvic pain. What type of surgery depends on the diagnosis. Surgery such as laparoscopy can be done on an outpatient basis, while other surgeries such as hysterectomy require a stay in the hospital. Your healthcare provider will discuss your options based on your diagnosis, as well as the risks and benefits of these procedures and the chance of them working. Hysterectomy is not always the best treatment, especially in the case of chronic pelvic pain.

Other treatments include heat therapy, muscle relaxants, nerve blocks, and relaxation exercises. If digestive or urinary conditions are diagnosed specific treatments for these conditions will be used.

Determining the cause of pelvic pain can be a frustrating situation for many women, but try not to give up. Even when one specific cause for chronic pelvic pain is not found your healthcare provider has treatments that can help. Maintaining an open working relationship with your physician is the best way to find the treatment that works best for you.

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) is the most common cause of abnormal vaginal bleeding during a woman's reproductive years. The diagnosis of DUB should be used only when other organic and structural causes for abnormal vaginal bleeding have been ruled out.

A normal menstrual cycle occurs every 21-35 days with menstruation for 2-7 days. The average blood loss is 35-150 mL total, which represents 8 or fewer soaked pads per day with usually no more than 2 heavy days.

During the normal menstrual cycle, the first day corresponds to the first day of menses. The menstrual phase usually lasts 4 days and involves the disintegration and sloughing of the functionalis layer of the endometrium. The proliferation (follicular) phase extends from day 5 to day 14 of the typical cycle. It is marked by endometrial proliferation brought on by estrogen stimulation. The estrogen is produced by the developing ovarian follicles under the influence of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Cellular proliferation of the endometrium is marked, and the length and convoluted nest of the spiral arteries increases. This phase ends as estrogen production peaks, triggering the FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) surge.

Rupture of the ovarian follicle follows, with the release of the ovum (ovulation). The secretory (luteal) phase is marked by the production of progesterone and less potent estrogens by the corpus luteum. It extends from day 15 to day 28 of the typical cycle. The functionalis layer of the endometrium increases in thickness and the stroma becomes edematous. If pregnancy does not occur, the estrogen and progesterone feedback to the hypothalamus, and FSH and LH production falls. The spiral arteries become coiled and have decreased flow. At the end of the cycle, they alternately contract and relax, causing a breakdown of the functionalis layer and menses to begin.

Approximately 90% of DUB results from anovulation and 10% occur with ovulatory cycles. During an anovulatory cycle, the corpus luteum fails to form, which causes failure of normal cyclical progesterone secretion. This results in continuous unopposed production of estradiol, stimulating overgrowth of the endometrium. Without progesterone, the endometrium proliferates and eventually outgrows its blood supply, leading to necrosis. The end result is an overproduction of uterine blood flow.

In ovulatory DUB, prolonged progesterone secretion causes irregular shedding of the endometrium. This probably is related to a constant low level of estrogen that is around the bleeding threshold. This causes portions of the endometrium to degenerate and results in spotting. Progesterone causes the enzymatic conversion of estradiol to estrone, a less potent estrogen. The changes in the endometrium remain secretory within the glands. Patients who exhibit these symptoms in the reproductive years often have ovulatory cycles or secondary reasons for altered hypothalamic function (eg, polycystic ovary disease).

Dysfunctional bleeding from the uterus can be described as follows:

* Menorrhagia - Prolonged (>7 d) or excessive (>80 mL daily) uterine bleeding occurring at regular intervals

* Metrorrhagia - Uterine bleeding occurring at irregular and more frequent than normal intervals

* Menometrorrhagia - Prolonged or excessive uterine bleeding occurring at irregular and more frequent than normal intervals

* Intermenstrual bleeding (spotting) - Uterine bleeding of variable amounts occurring between regular menstrual periods

* Polymenorrhea - Uterine bleeding occurring at regular intervals of less than 21 days

* Oligomenorrhea - Uterine bleeding occurring at intervals of 35 days to 6 months

* Amenorrhea - No uterine bleeding for 6 months or longer

The major categories of DUB include the following:

* Estrogen breakthrough bleeding

* Estrogen withdrawal bleeding

* Progestin breakthrough bleeding

As many as 10% of women with normal ovulatory cycles reportedly have experienced DUB. Obese females tend to have irregularities in their menstrual cycles due to nonovarian endogenous production of estrogen often related to their degree of adipose tissue. This usually results in prolonged cycles of amenorrhea that alternate with cycles of metrorrhagia or menometrorrhagia.

International

No cultural predilection is present with this disease state. However, note that countries, including the United States, that have a large population of female athletes have more recognition of this entity. In athletes, a loss of the LH surge, as well as, a luteal phase deficiency tends to be present. This is characterized by a shortened luteal phase from insufficient progesterone production or effect. This inadequate progesterone stimulation may be coexistent with high, low, or normal estrogen levels and often results in similar problems in anovulatory cycles such as amenorrhea.

Mortality/Morbidity

Morbidity is related to the amount of blood loss at the time of menstruation, which occasionally is severe enough to cause hemorrhagic shock.

Although, DUB in itself is rarely fatal, distinguishing this presentation from that of endometrial cancer is important. Development of endometrial cancer is related to estrogen stimulation and endometrial hyperplasia. Symptoms include postmenopausal bleeding, which is usually considered cancer until proven otherwise.

Race

DUB has no predilection for race; however, black women have a higher incidence of leiomyomas and higher levels of estrogen. As a result, they are prone to experiencing more episodes of abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Age

DUB is most common at the extreme ages of a woman's reproductive years, either at the beginning or near the end, but it may occur at any time during her reproductive life.

* Most severe cases of DUB occur in adolescent girls during the first 18 months after the onset of menstruation, when their immature hypothalamic-pituitary axis may fail to respond to estrogen and progesterone, resulting in anovulation.

* In the perimenopausal period, DUB may be an early manifestation of ovarian failure causing decreased hormone levels or responsiveness to hormones, thus also leading to anovulatory cycles. In patients who are 40 years or older, the number and quality of ovarian follicles diminish. Follicles continue to develop but do not produce enough estrogen in response to FSH to trigger ovulation. The estrogen that is produced usually results in late-cycle estrogen breakthrough bleeding.

* Patients often present with complaints of amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, menorrhagia, or metrorrhagia. Ask patients to compare the number of pads or tampons used per day in a normal menstrual cycle to the number used at the time of presentation. The average tampon holds 5 mL of blood; the average pad holds 5-15 mL of blood.

* Occasionally, bleeding is profuse with associated signs and symptoms of hypovolemia, including hypotension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and pallor. These patients usually do not have vaginal or pelvic pain associated with bleeding episodes, and other systemic symptoms rarely are noted unless vaginal bleeding has an organic cause.

* A reproductive history should always be obtained, including the following:

* Menstrual regularity

* Last menstrual period (LMP), including flow and duration

* Gravida and para

* Previous abortion or recent termination of pregnancy

* Contraceptive use

* Questions about medical history should include the following:

* Signs and symptoms of hypovolemia

* Diabetes mellitus

* Hypertension

* Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism

* Liver disease

* Medication usage, including exogenous hormones, anticoagulants, aspirin, anticonvulsants, and antibiotics

* Alternative and complementary medicine modalities, such as herbs and supplements

Physical

* Initial evaluation should be directed at assessing patient's volume status and degree of anaemia. Examine for pallor and absence of conjunctival vessels to gauge anaemia.

* Patients who are hemodynamically stable require a pelvic speculum and bimanual examination to define the aetiology of vaginal bleeding. The examination should look for the following:

* Trauma to the vaginal walls or cervix

* Retained foreign body

* Cervical or vaginal laceration

* Bleeding from the cervical os

* Uterine or ovarian structural abnormalities may be noted on bimanual examination, but a negative examination is insensitive for finding abnormalities.

* Patients with hematologic pathology also may have cutaneous evidence of bleeding diathesis. Physical findings include petechiae, purpura, and mucosal bleeding (eg, gums) in addition to vaginal bleeding.

* Patients with liver disease that has resulted in a coagulopathy may manifest additional symptomatology because of abnormal hepatic function. Evaluate patients for spider angioma, palmar erythema, splenomegaly, ascites, jaundice, and asterixis.

* Women with polycystic ovary disease present with signs of hyperandrogenism, including hirsutism, obesity, and palpable enlarged ovaries.

* Hyperactive and hypoactive thyroid can cause menstrual irregularities. Patients may have varying degrees of characteristic vital sign abnormalities, eye findings, tremors, changes in skin texture, and weight change. Goiter may be present.

* Multiple organic pathologies can present as abnormal vaginal bleeding, including thrombocytopenia, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Cushing disease, liver disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and adrenal disorders.

* Pregnancy may be associated with vaginal bleeding that the patient may report as "abnormal" for her in terms of timing, amount, or duration.

* Trauma to the cervix, vulva, or vagina may cause abnormal bleeding.

* Carcinomas of the vagina, cervix, uterus, and ovaries always must be considered in patients with the appropriate history and physical exam.

* Other causes of DUB include structural disorders, such as functional ovarian cysts, cervicitis, endometritis, salpingitis, and leiomyomas.

* Polycystic ovary disease, vaginal infection, polyps, ectopic pregnancy, hydatidiform mole, blood dyscrasias, excessive weight gain, increased exercise performance, or stress may also contribute to DUB.

* Breakthrough bleeding may occur in patients taking oral contraceptives that have inadequate doses of estrogen and progestin for the patient.

* Intermenstrual bleeding may occur secondary to missed pills, varied ingestion times, and drug interactions.

* The most common drug interactions with OCPs occur with phenobarbital, carbamazepine, some penicillin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

* Breakthrough bleeding can indicate reduced birth control efficiency; therefore, advise using additional birth control methods until the next menstrual cycle begins.

* An iatrogenic cause of DUB is the use of progestin-only compounds for birth control. Medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera), a long-acting injection given every 3 months, inhibits ovulation. An adverse effect of this drug is prolonged uterine breakthrough bleeding; this may continue after discontinuation of the drug because of persistent anovulation. The Norplant system (surgically implanted levonorgestrel), which acts to block some but not all ovulatory cycles, has the same adverse effects as Depo-Provera.

* Contraceptive intrauterine devices (IUDs) can cause variable vaginal bleeding for the first few cycles after placement and intermittent spotting subsequently. The progesterone impregnated IUD (Mirena) is associated with less menometrorrhagia and usually results in secondary amenorrhea.

The first obstetrical use of ultrasound was in 1958. Over the past 25 years, ultrasound has become almost routine in the care of pregnant women. Ultrasound is a method of creating an image by "bouncing" sound waves off tissues. The current technology uses "real-time" ultrasound, meaning that you see the picture on a screen as it is obtained. These images can also be recorded digitally, on videotape, or in still photos.

Ultrasound in its current form seems to be completely safe for the fetus. No risks have been demonstrated in its 25 years of common use.

Obstetrical ultrasound can be performed trans-abdominally (TA-US) or trans-vaginally (TV-US).

Neither type of ultrasound should be painful, although sometimes the TA-US requires a full bladder, which can be uncomfortable.

This is a question that is being hotly debated: should ultrasound be routine, or used only if there are questions or problems with the pregnancy? While there isn't any research that has shown that babies do better with routine ultrasound, many practitioners (and many parents) still feel most comfortable if they have "seen" the fetus before birth. Routine ultrasound is believed to be safe, but there is a financial cost to ultrasound that may prevent it from being used on a routine basis.

Ectopic means "out of place." In an ectopic pregnancy, a fertilized egg has implanted outside the uterus. The egg settles in the fallopian tubes in more than 95% of ectopic pregnancies. This is why ectopic pregnancies are commonly called "tubal pregnancies." The egg can also implant in the ovary, abdomen, or the cervix, so you may see these referred to as cervical or abdominal pregnancies.

None of these areas has as much space or nurturing tissue as a uterus for a pregnancy to develop. As the fetus grows, it will eventually burst the organ that contains it. This can cause severe bleeding and endanger the mother's life. A classical ectopic pregnancy does not develop into a live birth.

Ectopic pregnancy can be difficult to diagnose because symptoms often mirror those of a normal early pregnancy. These can include missed periods, breast tenderness, nausea, vomiting, or frequent urination.

The first warning signs of an ectopic pregnancy are often pain or vaginal bleeding. You might feel pain in your pelvis, abdomen, or, in extreme cases, even your shoulder or neck (if blood from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy builds up and irritates certain nerves). Most women describe the pain as sharp and stabbing. It may concentrate on one side of the pelvis and come and go or vary in intensity.

Any of the following additional symptoms can also suggest an ectopic pregnancy:

* vaginal spotting

* dizziness or fainting (caused by blood loss)

* low blood pressure (also caused by blood loss)

* lower back pain

An ectopic pregnancy results from a fertilized egg's inability to work its way quickly enough down the fallopian tube into the uterus. An infection or inflammation of the tube might have partially or entirely blocked it. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can be caused by gonorrhoea or chlamydia, is a common cause of blockage of the fallopian tube.

Endometriosis (when cells from the lining of the uterus implant and grow elsewhere in the body) or scar tissue from previous abdominal or fallopian surgeries can also cause blockages. More rarely, birth defects or abnormal growths can alter the shape of the tube and disrupt the egg's progress.

If you arrive in the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain, you'll likely be given a urine pregnancy test. Although these tests aren't sophisticated, they are fast — and speed can be crucial in treating ectopic pregnancy.

If you already know you're pregnant, or if the urine test comes back positive, you'll probably be given a quantitative hCG test. This blood test measures levels of the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is produced by the placenta and appears in the blood and urine as early as 8 to 10 days after conception. Its levels double every 2 days for the first several weeks of pregnancy, so if hCG levels are lower than expected for your stage of pregnancy, one possible explanation might be an ectopic pregnancy.

You'll probably also get an ultrasound examination, which can show whether the uterus contains a developing fetus or if masses are present elsewhere in the abdominal area. But the ultrasound might not be able to detect every ectopic pregnancy. The doctor may also give you a pelvic exam to locate the areas causing pain, to check for an enlarged, pregnant uterus, or to find any masses.

Even with the best equipment, it's hard to see a pregnancy less than 5 weeks after the last menstrual period. If your doctor can't diagnose ectopic pregnancy but can't rule it out, he or she may ask you to return every 2 or 3 days to measure your hCG levels. If these levels don't rise as quickly as they should, the doctor will continue to monitor you carefully until an ultrasound can show where the pregnancy is.

Treatment of an ectopic pregnancy varies, depending on how medically stable the woman is and the size and location of the pregnancy.

Early ectopic pregnancy can sometimes be treated with an injection of methotrexate, which stops the growth of the embryo.

If the pregnancy is further along, you'll likely need surgery to remove the abnormal pregnancy. In the past, this was a major operation, requiring a large incision across the pelvic area. This might still be necessary in cases of emergency or extensive internal injury.

However, the pregnancy may sometimes be removed using laparoscopy, a less invasive surgical procedure. The surgeon makes small incisions in the lower abdomen and then inserts a tiny video camera and instruments through these incisions. The image from the camera is shown on a screen in the operating room, allowing the surgeon to see what’s going on inside of your body without making large incisions. The ectopic pregnancy is then surgically removed and any damaged organs are repaired or removed.

Whatever your treatment, the doctor will want to see you regularly afterwards to make sure your hCG levels return to zero. This may take several weeks. An elevated hCG could mean that some ectopic tissue was missed. This tissue may have to be removed using methotrexate or additional surgery.

Some women who have had ectopic pregnancies will have difficulty becoming pregnant again. This difficulty is more common in women who also had fertility problems before the ectopic pregnancy. Your prognosis depends on your fertility before the ectopic pregnancy, as well as the extent of the damage that was done.

The likelihood of a repeat ectopic pregnancy increases with each subsequent ectopic pregnancy. Once you have had one ectopic pregnancy, you face an approximate 15% chance of having another.

Who's at Risk for an Ectopic Pregnancy?

While any woman can have an ectopic pregnancy, the risk is highest for women who are over 35 and have had:

* PID

* a previous ectopic pregnancy

* surgery on a fallopian tube

* infertility problems or medication to stimulate ovulation

Some birth control methods can also affect your risk of ectopic pregnancy. If you get pregnant while using progesterone-only oral contraceptives, progesterone intrauterine devices (IUDs), or the morning-after pill, you might be more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy. Smoking and having multiple sexual partners also increases the risk of an ectopic pregnancy.

If you believe you're at risk for an ectopic pregnancy, meet with your doctor to discuss your options before you become pregnant. You can help protect yourself against a future ectopic pregnancy by not smoking and by always using condoms when you're having sex but not trying to get pregnant. Condoms can protect against sexually transmitted infections (STDs) that can cause PID.

If you are pregnant and have any concerns about the pregnancy being ectopic, talk to your doctor — it's important to make sure it's detected early. You and your doctor might want to plan on checking your hormone levels or scheduling an early ultrasound to ensure that your pregnancy is developing normally.

Call your doctor immediately if you're pregnant and experiencing any pain, bleeding, or other symptoms of ectopic pregnancy. When it comes to detecting an ectopic pregnancy, the sooner it is found, the better

About 20% of ovarian cancers are found at an early stage. When ovarian cancer is found early at a localized stage, about 94% of patients live longer than 5 years after diagnosis. Several large studies are in progress to learn the best ways to find ovarian cancer in its earliest stage.

During a pelvic exam, the health care professional feels the ovaries and uterus for size, shape, and consistency. A pelvic exam can be useful because it can find some reproductive system cancers at an early stage, but most early ovarian tumors are difficult or impossible for even the most skilled examiner to feel. Pelvic exams may, however, help identify other cancers or gynecologic conditions. Women should discuss the need for these exams with their doctor.

The Pap test is effective in early detection of cervical cancer, but it isn’t a test for ovarian cancer. Rarely, ovarian cancers are found through Pap tests, but usually, they are at an advanced stage.

See a doctor if you have symptoms.

Early cancers of the ovaries often cause no symptoms. When ovarian cancer causes symptoms, they tend to be symptoms that are more commonly caused by other things. These symptoms include abdominal swelling or bloating (due to a mass or a buildup of fluid), pelvic pressure or abdominal pain, difficulty eating or feeling full quickly, and/or urinary symptoms (having to go urgently or often). Most of these symptoms can also be caused by other less serious conditions. These symptoms can be more severe when they are caused by ovarian cancer, but that isn’t always true. What is most important is that they are a change from how a woman usually feels.

By the time ovarian cancer is considered as a possible cause of these symptoms, it usually has already spread beyond the ovaries. Also, some types of ovarian cancer can rapidly spread to the surface of nearby organs. Still, prompt attention to symptoms may improve the odds of early diagnosis and successful treatment. If you have symptoms similar to those of ovarian cancer almost daily for more than a few weeks, and they can't be explained by other more common conditions, report them to your health care professional -- preferably a gynaecologist -- right away.

Screening tests and exams are used to detect a disease, like cancer, in people who don’t have any symptoms. Perhaps the best example of this is the mammogram, which can often detect breast cancer in its earliest stage, even before a doctor can feel cancer. There has been a lot of research to develop a screening test for ovarian cancer, but there hasn’t been much success so far. The 2 tests used most often to screen for ovarian cancer are transvaginal ultrasound and the CA-125 blood test.

Transvaginal ultrasound is a test that uses sound waves to look at the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries by putting an ultrasound transducer into the vagina. It can help find a mass (tumour) in the ovary, but it can't actually tell if a mass is cancer or benign. When it is used for screening, most of the masses found are not cancer.

CA-125 is a protein in the blood. In many women with ovarian cancer, levels of CA-125 are high. This test can be useful as a tumour marker to help guide treatment in women known to have ovarian cancer because a high level often goes down if treatment is working.

But checking CA-125 levels has not been found to be as useful as a screening test for ovarian cancer. The problem with using this test for screening is that common conditions other than cancer can also cause high levels of CA-125. In women who have not been diagnosed with cancer, a high CA-125 level is more often caused by one of these other conditions and not ovarian cancer. Also, not everyone who has ovarian cancer has a high CA-125 level. When someone who is not known to have ovarian cancer has an abnormal CA-125 level, the doctor might repeat the test (to make sure the result is correct). The doctor could also consider ordering a transvaginal ultrasound test.

In studies of women at average risk of ovarian cancer, using transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 for screening led to more testing and sometimes more surgeries, but did not lower the number of deaths caused by ovarian cancer. For that reason, no major medical or professional organization recommends the routine use of transvaginal ultrasound or the CA-125 blood test to screen for ovarian cancer.

Some organizations state that these tests may be offered to screen women who have a high risk of ovarian cancer due to an inherited genetic syndrome. Still, even in these women, it’s not clear that using these tests for screening lowers their chances of dying from ovarian cancer.

Better ways to screen for ovarian cancer are being researched. Hopefully, improvements in screening tests will eventually lead to a lower ovarian cancer death rate.

There are no recommended screening tests for germ cell tumours or stromal tumours. Some germ cell cancers release certain protein markers such as human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) into the blood. After these tumours have been treated by surgery and chemotherapy, blood tests for these markers can be used to see if treatment is working and to determine if the cancer is coming back.

Researchers continue to look for new tests to help diagnose ovarian cancer early but currently, there are no reliable screening tests.

A BRCA mutation is a mutation in either of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which are tumour suppressor genes. Hundreds of different types of mutations in these genes have been identified, some of which have been determined to be harmful, while others as benign or of still unknown or uncertain impact. Harmful mutations in these genes may produce a hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome in affected persons. Only 5-10% of breast cancer cases in women are attributed to BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, but the impact on women with the gene mutation is more profound. Women with harmful mutations in either BRCA1 or BRCA2 have a risk of breast cancer that is about five times the normal risk, and risk of ovarian cancer that is about ten to thirty times normal.[2] The risk of breast and ovarian cancer is higher for women with a high-risk BRCA1 mutation than with a BRCA2 mutation. Having a high-risk mutation does not guarantee that the woman will develop any type of cancer, or imply that any cancer that appears was actually caused by the mutation, rather than some other factor.

Genetic counselling is commonly recommended to people whose personal or family health history suggests a greater than average likelihood of a mutation. Genetic counsellors are allied health professionals who are trained to explain genetics to people; some of them are also licensed as registered nurses or social workers. A medical geneticist is a physician who specializes in genetics. The purpose of genetic counselling is to educate the person about the likelihood of a positive result, the risks and benefits of being tested, the limitations of the tests, the practical meaning of the results, and the risk-reducing actions that could be taken if the results are positive. They are also trained to support people through any emotional reactions and to be a neutral person who helps the client make his or her own decision in an informed consent model, without pushing the client to do what the counsellor might do. Because the knowledge of a mutation can produce substantial anxiety, some people choose not to be tested or to postpone testing until a later date.

Relative indications for testing for a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 include a family history among 1st, 2nd, or 3rd-degree relatives in either lineage with any of the following:

Breast cancer diagnosed at age 50 or younger

Ovarian cancer

Multiple primary breast cancers either in the same breast or opposite breast in an individual

Both breast and ovarian cancer

Male breast cancer

Triple-negative (estrogen receptor-negative, progesterone receptor-negative, and HER2/neu negative) breast cancer

Pancreatic cancer with breast or ovarian cancer in the same individual or on the same side of the family

Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry

Two or more relatives with breast cancer, one under age 50

Three or more relatives with breast cancer at any age

A previously identified BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation in the family

Testing young children is considered medically unethical because the test results would not change the way the child's health is cared for.

If the client chooses to be tested, then two types of tests are available. Both commonly use a blood sample, although testing can be done on saliva. The quickest, simplest, and lowest cost test uses positive test results from a blood relative and checks only for the single mutation that is known to be present in the family. If no relative has previously disclosed positive test results, then a full test that checks the entire sequence of both BRCA1 and BRCA2 can be performed. In some cases, because of the founder effect, Jewish ethnicity can be used to narrow the testing to quickly check for the three most common mutations seen among Ashkenazi Jews.

Testing is commonly covered by health insurance and public healthcare programs for people at high risk for having a mutation, and not covered for people at low risk. The purpose of limiting the testing to high-risk people is to increase the likelihood that the person will receive a meaningful, actionable result from the test, rather than identifying a variant of unknown significance (VUS). In Canada, people who demonstrate their high-risk status by meeting specified guidelines are referred initially to a specialized program for hereditary cancers, and, if they choose to be tested, the cost of the test is fully covered. In the USA in 2010, single-site testing had a retail cost of US$400 to $500, and full-length analysis cost about $3,000 per gene, and the costs were commonly covered by private health insurance for people deemed to be at high risk.

The test is ordered by a physician, usually an oncologist, and the results are always returned to the physician, rather than directly to the patient. How quickly results are returned depends on the test—single-site analysis requires less lab time—and on the infrastructure in place. In the USA, test results are commonly returned within one to several weeks; in Canada, patients commonly wait for eight to ten months for test results.

A positive test result for a known deleterious mutation is proof of a predisposition, although it does not guarantee that the person will develop any type of cancer. A negative test result, if a specific mutation is known to be present in the family, shows that the person does not have a BRCA-related predisposition for cancer, although it does not guarantee that the person will not develop a non-hereditary case of cancer. By itself, a negative test result does not mean that the patient has no hereditary predisposition for breast or ovarian cancer. The family may have some other genetic predisposition for cancer, involving some other gene.